While I saved and planned my departure for Mauritius I felt like I was in an extreme delayed gratification study, staring at a mango on a plate for months on end. Why not stay home? What is the sense in all of this wandering? Why is there so much joy for me in caroming off in an unknown direction? My drive to undertake adventures and explore the unknown has always been hard to explain.

On the plane to Paris I wrote the following: “For me it seems that adventures and the mystery of life unfolding are the single greatest joys in life. There will always be sedentary jobs, possessions to accumulate, things to be learned through perseverance, and debts to amass and service. Death will always haunt us as an omnipresent specter though. The potential ways to live a life seem as limitless like the earth itself. Maybe I am just not meant to sit and work in – as Mark Salouka says – paint factories. I sleep better under the stars. I feel best when I rise with the sun. I often find myself want to run wild and break from the rational non-sense of society. Another justification seems to lie in my perception that society, science, religion, and technology fail to explain the mystery of mysteries. Exploring seems to be the realization of my philosophy regarding life in some way. It could be said to be pointless, self-serving, futile… but this logic can be turned against most of the activities that other people spend their lives doing whether it is working for a financial services company, designing multi-billion dollar Iphone applications that allow teenagers to send one another self-destructing photos of their genitals, of wealth accumulation, or of working in a paint factory.”

On the plane to Paris I wrote the following: “For me it seems that adventures and the mystery of life unfolding are the single greatest joys in life. There will always be sedentary jobs, possessions to accumulate, things to be learned through perseverance, and debts to amass and service. Death will always haunt us as an omnipresent specter though. The potential ways to live a life seem as limitless like the earth itself. Maybe I am just not meant to sit and work in – as Mark Salouka says – paint factories. I sleep better under the stars. I feel best when I rise with the sun. I often find myself want to run wild and break from the rational non-sense of society. Another justification seems to lie in my perception that society, science, religion, and technology fail to explain the mystery of mysteries. Exploring seems to be the realization of my philosophy regarding life in some way. It could be said to be pointless, self-serving, futile… but this logic can be turned against most of the activities that other people spend their lives doing whether it is working for a financial services company, designing multi-billion dollar Iphone applications that allow teenagers to send one another self-destructing photos of their genitals, of wealth accumulation, or of working in a paint factory.”

But I am not alone. About 3500 years ago it is estimated that Pacific Islanders expanded their territory to islands that would require up to several weeks on the open sea to reach. What made them go into the blue unknown in search of islands that they didn’t even know existed? About 15,000 years ago the first waves of explorers are estimated to have crossed the Bering land bridge and roamed across two new continents. What made them go out into that white unknown of ice and snow?

I recently read a book titled ‘The Song of the Dodo’ by David Quammen, a tome on the history of evolutionary biology and it was there I stumbled across the idea that maybe this part of me is not unique. It appears that many scientists believe that this nagging curiosity is a defining characteristic of homo sapiens. In conjunction with the development of our complex brains and limbs seems to have come about a set of traits that helped us expand out of Africa and to ultimately inhabit almost every tract of land on this planet in about 60,000 years. These traits drove us far and wide; we crossed open seas on boats, we walked across land bridges, we floated down rivers, we flew planes.

Not every species shares this same propensity though. There are others, like the Mauritian Kestrel, that refuse to even cross small clearings in the forest. There must be evolutionary environments and genetic endowments that reinforce this trait and others that would make it a disadvantage. Explorers of any species have the ability to sow their seed far and wide. An adaptable generalist species would seemingly benefit from this trait and reinforce it as more progeny means a higher proportion of a particular set of genes in the pool.

Not every species shares this same propensity though. There are others, like the Mauritian Kestrel, that refuse to even cross small clearings in the forest. There must be evolutionary environments and genetic endowments that reinforce this trait and others that would make it a disadvantage. Explorers of any species have the ability to sow their seed far and wide. An adaptable generalist species would seemingly benefit from this trait and reinforce it as more progeny means a higher proportion of a particular set of genes in the pool.

I began doing a bit of research and stumbled across an interesting National Geographic Article entitled ‘Restless Genes.’ The author, David Dobbs, expands upon this idea. Here is an excerpt about the gene DRD4-7R:

“If an urge to explore rises in us innately, perhaps its foundation lies within our genome. In fact there is a mutation that pops up frequently in such discussions: a variant of a gene called DRD4, which helps control dopamine, a chemical brain messenger important in learning and reward. Researchers have repeatedly tied the variant, known as DRD4-7R and carried by roughly 20 percent of all humans, to curiosity and restlessness. Dozens of human studies have found that 7R makes people more likely to take risks; explore new places, ideas, foods, relationships, drugs, or sexual opportunities; and generally embrace movement, change, and adventure. Studies in animals simulating 7R’s actions suggest it increases their taste for both movement and novelty.”

And this part strikes home for me, it seems to be a natural corollary to the idea of a restless gene:

“Among Ariaal tribesmen in Africa, those who carry 7R tend to be stronger and better fed than their non-7R peers if they live in nomadic tribes, possibly reflecting better fitness for a nomadic life and perhaps higher status as well. However, 7R carriers tend to be less well nourished if they live as settled villagers. The variant’s value, then, like that of many genes and traits, may depend on the surroundings. A restless person may thrive in a changeable environment but wither in a stable one; likewise with any genes that help produce the restlessness.”

“Among Ariaal tribesmen in Africa, those who carry 7R tend to be stronger and better fed than their non-7R peers if they live in nomadic tribes, possibly reflecting better fitness for a nomadic life and perhaps higher status as well. However, 7R carriers tend to be less well nourished if they live as settled villagers. The variant’s value, then, like that of many genes and traits, may depend on the surroundings. A restless person may thrive in a changeable environment but wither in a stable one; likewise with any genes that help produce the restlessness.”

I have always been looking for ways to justify this part of myself, but maybe it is just genetic , maybe it isn’t something that can be subjected to analysis. I think it may have been said best by Hank Williams:

“I can settle down and be doin’ just fine

Til I hear an old train rollin’ down the line

Then I hurry straight home and pack

And if I didn’t go, I believe I’d blow my stack

I love you baby, but you gotta understand

When the lord made me

He made a ramblin’ man.

Some folks might say that I’m no good

That I wouldn’t settle down if I could

But when that open road starts to callin’ me

There’s somethin’ o’er the hill that I gotta see.”

Rambling

My papers were not quite on the up and up, so I shaved my face and cut my hair. I put on a button down shirt, khakis, and placed two pens in my front pocket to lend myself legitimacy under the weary eye of the immigration officials in Mauritius. At this point in my life I can confidently say that I understand bureaucracy pretty well, so I printed out – in triplicate – any and all documents, regardless of how superfluous, that had a seal, signature, or my name on them. On the way from Salt Lake City to Mauritius via Paris I wielded these papers like a weapon no less than three times. I think that their efficacy lies in their threat of monotony.

I approached the immigration desk in Mauritius calmly and told the woman the following after our pleasantries, “The government just said to give me a tourist visa until they finish processing my visa application.” See what I did there? I presented the outcome that I wanted with no other options. I avoided the hours of waiting in queues that I had heard of others experiencing in similar situations.

I approached the immigration desk in Mauritius calmly and told the woman the following after our pleasantries, “The government just said to give me a tourist visa until they finish processing my visa application.” See what I did there? I presented the outcome that I wanted with no other options. I avoided the hours of waiting in queues that I had heard of others experiencing in similar situations.

The only problem though was that she handed back my passport and then looked up from her papers and asked, “Which company is it that you normally work for here?”

I stumbled here, “I don’t work…for…I have never been here before.”

She stumbled, looked both directions, and then said, “Oh..okay. Well thank you, bye bye.”

I had a 30 day business visa instead of a 90 day tourist visa. I cursed the two pens in my front pocket.

Impressions

I had spent so much time reading academic papers and books about Mauritius, examining numbers that attempted to quantify it, and analyses of its problems that I arrived with a brain filled with sociological mush without a pinch of reality. There are no measures of net beauty, blissful slumber opportunities per capita, food deliciousness index (FDI), gross hammock oscillations per hour, or gross domestic laughter. But I think that Mauritius would score high on all of these measures. There are also never any news stories announcing that the world is okay or exhorting us to do nothing as an overwhelming wave of peace has swept through the region. The remedy for this condition is to taste the mango.

The birds wake me each morning with the rising of the sun. Mangos are falling off of the trees on our street and my only competition is the birds. A pack of family dogs patrols the street outside our apartment. I pass my first days lazing around in

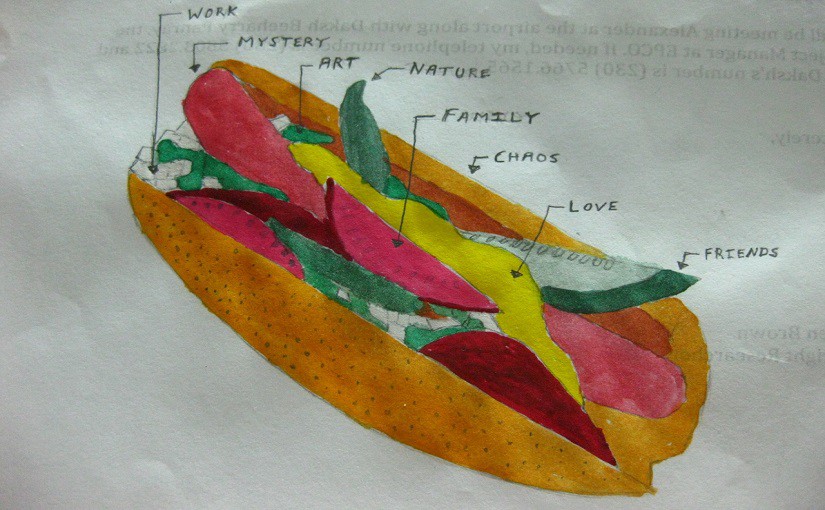

The birds wake me each morning with the rising of the sun. Mangos are falling off of the trees on our street and my only competition is the birds. A pack of family dogs patrols the street outside our apartment. I pass my first days lazing around in  and about the turquoise sea that merges with the sky if you screw your eyes up in just the right way. I still have not seen a jet ski in Mauritius and I could count on one hand the number of guns that I have seen – both things bode well for a country in my mind. The people are amazing here – friendly, content, and welcoming. Culturally, it is midway between Europe, Africa, India, and China. You hear it when people speak and in the food you eat. Roti – the national dish of sorts – is the best food in the world rupee for rupee. It consists of a fried flour wrap filled with assorted sauces, chilis, and curries that is readily available whenever necessary. Mauritius is a sauce country, this seems to exemplify its culture to me.

and about the turquoise sea that merges with the sky if you screw your eyes up in just the right way. I still have not seen a jet ski in Mauritius and I could count on one hand the number of guns that I have seen – both things bode well for a country in my mind. The people are amazing here – friendly, content, and welcoming. Culturally, it is midway between Europe, Africa, India, and China. You hear it when people speak and in the food you eat. Roti – the national dish of sorts – is the best food in the world rupee for rupee. It consists of a fried flour wrap filled with assorted sauces, chilis, and curries that is readily available whenever necessary. Mauritius is a sauce country, this seems to exemplify its culture to me.

We visited the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden and saw a dozen or so tortoises imported from all over region. Despite their ersatz environment, I was mesmerized by their beauty as they charged at us from the other side of the pen after their lunch was delivered. The largest was 150 years old. It was nearly as interested to watch the packs of French tourists touting IPads descend upon the pen.

We visited the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Botanical Garden and saw a dozen or so tortoises imported from all over region. Despite their ersatz environment, I was mesmerized by their beauty as they charged at us from the other side of the pen after their lunch was delivered. The largest was 150 years old. It was nearly as interested to watch the packs of French tourists touting IPads descend upon the pen.

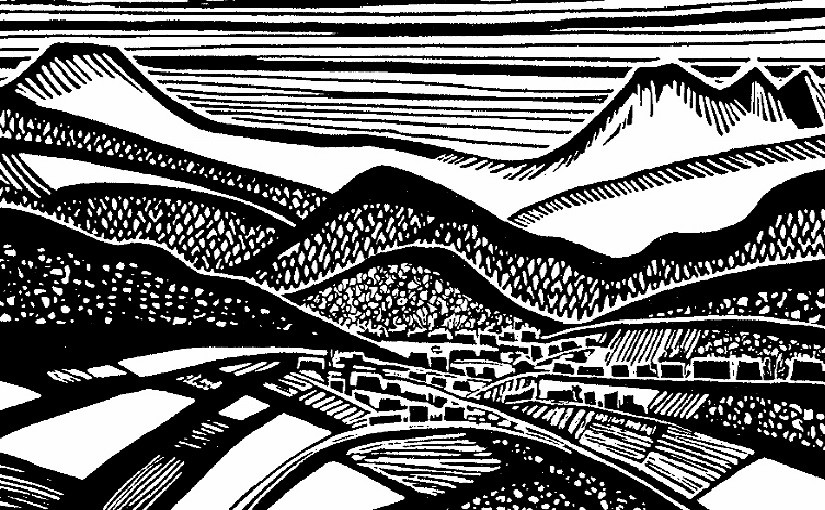

We bought a Suzuki motorcycle with 125cc’s of Merlot colored fossil fueled fury. I turned 30 and wanted to go explore the southern part of the island for my birthday. I turned out into the left lane and we started the epic 40 mile journey south on the main highway. Rain began to fall on us early on as midday clouds gathered around the pinnacles of the Moka Mountains. The mountains rise as forested islands in the midst of a boundless expanse of green sugarcane not unlike the blue sea that the islands of Mauritius rise up from. It felt like we were flying with the engine roaring; I wanted to howl and make obscene gestures at the elderly, until a pair of them passed us in their miniature car going twice our speed. We passed mansions on dirt roads in the middle of nowhere, slums, dilapidated colonial buildings, gleaming skyscrapers, textile mills, and a tuna cannery. I muscled the bike through the concrete tandoori oven called Port Louis by splitting through traffic and riding the shoulder. Lauren complemented me on my driving with a flattering comparison to a fictional symbol of masculinity and daring from Hollywood, but I self-effacingly deflected the remark by comparing myself to a cat on a skateboard acting on pure fight or flight responses. We stayed at a friend’s place in Flic-en-Flac, a coastal town along the west coast.

The mountains around the island are all remnants of the giant caldera that formed the island and then collapsed. Black River Gorges National Park encompasses the majority of the mountains on the southern part of the island. It also happens to contain some of the last remaining old growth forest – less than 2% of it remains on the island – and consequently the majority of the remnant populations of many endemics like the Mauritius Kestrel, Mauritian Flying Fox, Pink Pigeon, and Echo Parakeet. The Mauritius Kestrel population was as low as four individuals in 1974 – the rarest bird on earth at the time. The numbers have rebounded, but remain modest. There is a limited amount that can be done when the primary problems that a species faces are habitat fragmentation and destruction.

The mountains around the island are all remnants of the giant caldera that formed the island and then collapsed. Black River Gorges National Park encompasses the majority of the mountains on the southern part of the island. It also happens to contain some of the last remaining old growth forest – less than 2% of it remains on the island – and consequently the majority of the remnant populations of many endemics like the Mauritius Kestrel, Mauritian Flying Fox, Pink Pigeon, and Echo Parakeet. The Mauritius Kestrel population was as low as four individuals in 1974 – the rarest bird on earth at the time. The numbers have rebounded, but remain modest. There is a limited amount that can be done when the primary problems that a species faces are habitat fragmentation and destruction.

We packed up early and left to explore the park. As we drove into the park a mongoose slinked across the road a disappeared into the brush. The mongoose was intentionally released by the government to help control disease bearing rodents, despite the knowledge that it had previously wreaked havoc elsewhere. It was less than a decade before the government was striving to eradicate the mongoose after it decided that chickens and all manner of other animals were as good as or better than rats.

We packed up early and left to explore the park. As we drove into the park a mongoose slinked across the road a disappeared into the brush. The mongoose was intentionally released by the government to help control disease bearing rodents, despite the knowledge that it had previously wreaked havoc elsewhere. It was less than a decade before the government was striving to eradicate the mongoose after it decided that chickens and all manner of other animals were as good as or better than rats.

We walked several well groomed but poorly marked trails that switchbacked up the mountainside. All of the forest through which we passed appeared to have been logged at some point. I didn’t notice it until a few hours had passed, but the forest seemed impoverished of insects; I saw a few butterflies and dragonflies, but not much else. We reached a lookout and looked down valley upon the sea. A few white Tropic Birds with their tendril tails rode currents below us. I paced around the overlook trying to take in everything and then suddenly I saw two bright green birds streak across below me. I tried to contain my giddiness as I hollered for Lauren to come see the Echo Parakeets. The parakeet had rebounded from as few as ten individuals to as many as 300 through the remarkable efforts of a few dedicated conservationists, in fact the same ones that saved the Kestrel. We looped back and hopped on the motorcycle. I hooted in my helmet as a Crab Eating Macaque loped across the road in front of us as we rode back to Flic-en-Flac.

Octopus Project

We awoke at 5:45 the following morning to return to Pereybere and then catch a ride to the east side of the island where we had a meeting to examine a UN GEF funded project building octopus burrows for fisherfolk out of reclaimed telephone poles. The director of the organization in charge of the program, Environmental Protection and Conservation Organization (EPCO), explained that the program arose after declining fish catches drove many fisherfolk to work for the government mining sand to feed the insatiable demand for concrete on this nearly treeless island. (The concept of sand mining is possibly a better example of a mind numbing and endless task than working in a paint factory.) The problems with sand mining eventually became apparent and the industry shifted to the crushing of mined rocks. This left many fishermen out of work with few directions to turn. The octopus burrow project was designed to both help rehabilitate the fishery and help sustain the fisherfolk. We wanted to see how it was working.

We awoke at 5:45 the following morning to return to Pereybere and then catch a ride to the east side of the island where we had a meeting to examine a UN GEF funded project building octopus burrows for fisherfolk out of reclaimed telephone poles. The director of the organization in charge of the program, Environmental Protection and Conservation Organization (EPCO), explained that the program arose after declining fish catches drove many fisherfolk to work for the government mining sand to feed the insatiable demand for concrete on this nearly treeless island. (The concept of sand mining is possibly a better example of a mind numbing and endless task than working in a paint factory.) The problems with sand mining eventually became apparent and the industry shifted to the crushing of mined rocks. This left many fishermen out of work with few directions to turn. The octopus burrow project was designed to both help rehabilitate the fishery and help sustain the fisherfolk. We wanted to see how it was working.

We boarded a handmade wooden boat with a fisherman named Dost – a Creole word that means friend. We puttered out towards the surging whitewash of the reef break and looked back upon the Bambous Mountains above Grand Reviere Sud Este. The water was absolutely clear and less than two meters deep. I leaned over the gunwale, which listed the boat to one side, in order to peer down at the kaleidoscope of coral.

We boarded a handmade wooden boat with a fisherman named Dost – a Creole word that means friend. We puttered out towards the surging whitewash of the reef break and looked back upon the Bambous Mountains above Grand Reviere Sud Este. The water was absolutely clear and less than two meters deep. I leaned over the gunwale, which listed the boat to one side, in order to peer down at the kaleidoscope of coral.

I jumped into the other splendorous world that covers 70% of the earth’s surface and stuck my snorkel in my mouth. The fish seemed sentient and curious as we examined one another. They let me get close to admire their incredible forms and scintillating scales, and colors that surely exist nowhere else. The fish would disappear and reappear as they wove their way through corals with shapes that seem floral, cerebral, and dendritic. I found one large lobed brain that teemed with a miniature microcosm of colored fish. I gestured Lauren over and we relished the beauty of it in a complete absence of words.

Dost gestured us over and we followed him over to an octopus burrow. He began prodding into the burrow with a rod and drew an ink spraying ball of arms out that he grabbed as it tried to make its Houdini-esque escape. It grabbed onto his arm and he repeatedly had to tear it loose. I stared with rapt attention as it furiously changed colors and patterns. He let it swim for a moment and it descended to the bottom, felt around, shrunk its size, and changed to match its surroundings. It is not just an octopus. The symbol ‘octopus’ does not begin to convey the beauty and complexity of that animal. Nor does ‘coral reef’ begin to encompass what I saw.

Dost gestured us over and we followed him over to an octopus burrow. He began prodding into the burrow with a rod and drew an ink spraying ball of arms out that he grabbed as it tried to make its Houdini-esque escape. It grabbed onto his arm and he repeatedly had to tear it loose. I stared with rapt attention as it furiously changed colors and patterns. He let it swim for a moment and it descended to the bottom, felt around, shrunk its size, and changed to match its surroundings. It is not just an octopus. The symbol ‘octopus’ does not begin to convey the beauty and complexity of that animal. Nor does ‘coral reef’ begin to encompass what I saw.

I identify with that octopus – how it changes to reflect its environment and how it strives to defend itself by spraying ink. I think that I might be doing that right now. We ate it later.

doing what I enjoyed. I set about exploring the scattered remnants of natural areas on the island. I found happiness in the quiet of the forest and the inspiration on the peaks. I breathed deeply in the open, relishing the reprieve from the oppressive concrete sprawl and sugarcane wastes. It did not take long before I had hiked all of the well-known trails and peaks. I began scouring the internet and asking around to uncover new frontiers. I began bringing my GPS with me, taking photos, and writing about the trails. I hiked during cyclones in the howling winds and rain. I baked my arms in the tropical sun and came home sliced to bits by vicious tropical plants.

doing what I enjoyed. I set about exploring the scattered remnants of natural areas on the island. I found happiness in the quiet of the forest and the inspiration on the peaks. I breathed deeply in the open, relishing the reprieve from the oppressive concrete sprawl and sugarcane wastes. It did not take long before I had hiked all of the well-known trails and peaks. I began scouring the internet and asking around to uncover new frontiers. I began bringing my GPS with me, taking photos, and writing about the trails. I hiked during cyclones in the howling winds and rain. I baked my arms in the tropical sun and came home sliced to bits by vicious tropical plants. The number of people who use the website and are getting outside is growing every week. I stumbled into doing exactly what I intended to do at the outset.

The number of people who use the website and are getting outside is growing every week. I stumbled into doing exactly what I intended to do at the outset.